by Garrett Caples

San Francisco Bay Guardian July 6, 2005

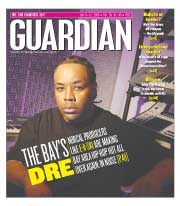

I'M FOLLOWING E-A-Ski's black Mercedes at a brisk clip through the winding turns of the Oakland Hills, en route to our interview.

Suddenly we plunge down a steep, straight road lined by two rows of enormous trees, like we were on our way to stately Wayne Manor but accidentally took the secret path to the Batcave. Our destination involves a little of both, for the immense, shingled affair, whose overall shape I can't quite determine, serves as residence and laboratory for an undeniably dynamic duo. Ski's cousin and coproducer, CMT – who combines the easy camaraderie of Robin with the quiet discretion of Alfred – later describes the house as having a "log-cabin feel," which, compared to any of the more vertically oriented mansions in the immediate vicinity, it does. But its size and weathered-wood exterior more readily recall a small sawmill, bent to a purpose alien to the more stockbrokerly pursuits of its neighbors.

CMT is already in the lab working when we arrive. The "lab" in question is a studio – not a home studio or preproduction studio, but a fully equipped, 32-track, take-it-from-here-and-press-it-up professional recording studio, the needs of which clearly dictate the house's design, an ocean-liner layout of skinny corridors surrounding large interior rooms. Built at the pair's behest 11 years ago with proceeds from a million-dollar deal with Priority for an album that never came out, the structure is a monument to Ski's business acumen, to the "Excellent Ability to stay on top" embodied in his initials. "Skiing" is Ski's metaphor for this, and it's apt, for Ski has skied through the wreckage of no less than four such deals.

Obstacles that have sent other careers into free fall have only launched Ski and CMT into higher tax brackets. In 1998, for example, when DreamWorks refused to release his completed second album, Earthquake, unless he added a track with an artist from the newly hot Dirty South, Ski forced the company into a breach-of-contract settlement. "A big settlement," he adds, not with relish or bitterness so much as a sense of outraged honor appeased by appropriate compensation.

Yet Ski's refusal to be ensnared in industry machinations has come at a cost. Platinum-hit makers since their first major label production – Spice One's "Trigger Gots No Heart," from the 1993 Menace II Society soundtrack (Jive) – the duo's extensive list of big-name clientele includes E-40, Ice Cube, even the almighty Dr. Dre himself. But Ski's own output as an artist has been limited to a handful of fugitive releases; he has yet to drop a proper solo album (one can't count the now-out-of-print 2003 limited-edition mix tape, Past and Present). Now, with a new distribution deal for his Infrared Music Group through Penalty/Rykodisc, and a hot young act, the Frontline, on his hands, Ski is putting the finishing touches on Apply Pressure, his debut and masterpiece rolled into one. Begun in 1998 as Aftershock – the follow-up to Earthquake (which was never released due to the dissolution of Relativity) and his 1992 EP, 1 Step Head of Yall (No Limit) – Apply Pressure has already spawned two hit singles, "Ride," in 2003, and "My Bad," from earlier this year. Given the current momentum of Bay Area hip-hop in terms of signings and airplay, a momentum he's had no small role in generating, the time is ripe for the Chronic-level event that Apply Pressure threatens to be. More than a dozen years into his career, will Ski finally release the classic he's always said he would?

The negotiator

Born Shon LaAnthony Adams and raised in East Oakland, E-A-Ski drives a hard bargain; it took no end of negotiations just to get me here. But Ski is more than ready to deliver: During the next two hours, under the attentive, confirming eye of CMT, he unreels enough material to fill several volumes. By turns guarded and unguarded, coolly rational and bubbling with an anger for which his raps serve as a therapeutic release, Ski is nothing if not complex. And productive: He and C claim a total of 15 million records sold, and with all the gold and platinum on the walls, I don't need to inspect the books.

"We're not young like we used to be," says the 30-year-old Ski. "We don't dictate the music. We have to make sure that we revolve around whatever the kids is liking." To this end, the producers do their "homework," bringing fresh tracks to the hood and playing them for kids in the 12- to 17-year-old range. They also study whatever music is popular. "We don't make music that's personal. We might not even like the stuff that's winning but we're like, I can see why this sound is moving the younger audience."

Such methodical research has helped Ski and C stay on top of hip-hop's constantly shifting terrain. Their consistent hit-making ability as producers has allowed them to achieve amicable resolutions when deals haven't turned out to their satisfaction. Apart from the contractual dispute with DreamWorks, whenever they've lost faith in a company's direction, they've been able to withdraw on good terms, using production to offset any advances.

"None of these companies were bad companies," Ski insists. "But ... wrong timing. With Priority in '94, everything was going right until they merged with EMI. So we opted out. Relativity was closed down because it was bought out. Columbia in 2001 did a merger and fired the A and R person who brought us there. But we've been fortunate because we've been able to use our production to leverage my situation as an artist."

Major label signees would do well to pause here and study Ski's game before buying that diamond-crusted bezzle they always wanted. Studio time is expensive – the primary expense of making albums – but once they'd built their own, Ski and C used it to work off the advance they'd used to pay for it, without having to spend their own money. After that, free studio. Free money-making machine. Not to mention a place to live. You don't need to be a college graduate, like College of Alameda alum Ski, to appreciate the economics of this arrangement.

"That's one of the things me and CMT did: We invested in our future," Ski explains. "We were smart. Our parents were smart. We can't say we don't have nothing to fall back on like property because we invested in dumb shit."

Rap dreams

After Columbia became the fourth consecutive label to sign him without releasing an album, a less stoic soul might have consoled himself by dropping his own records locally, or even settling into the lucrative and enviable position of a nationally recognized A-list hip-hop production team. Yet I doubt this is possible in E-A-Ski's case. His desire to rock the mic is undiminished from the days when he and CMT were in the basement rehearsing routines copped from a live tape of Run-DMC. And this hunger, more than any other single factor, seems to motivate the pair's rigorous quest to stay current in an age-conscious industry where short careers are the norm.

But rather than immediately shop for another deal, Ski decided to switch tactics "to show how you could make records without being under a major situation and get your community to support them." This campaign took two fronts, one of which, appropriately enough, was the Frontline: Left and Locksmith. Impressed by Locksmith's famous Bay-repping performance during MTV's 2003 freestyle competition, Ski subsequently met the Richmond rappers through MC Balance, a mutual friend. "They had great attitudes," Ski says. "They didn't smoke, didn't drink – they were focused, going to school. It was a great combination." The equally abstemious Ski and CMT quickly clicked with the Frontline, signing them to IMG, and moving around 10,000 units of their locally released debut, Who R You (2004). Fusing Left's own idiosyncratic, rock-influenced productions onto a solid backbone of E-A-Ski/CMT bangers, Who R You was sufficient proof of Ski's continued viability for Penalty/Rykodisc to sign on as distributor for the entire IMG label.

"I see what Ski is doing," veteran East Palo Alto rapper-producer Sean T says. "He's integrating Frontline with himself to bring himself back out there and let people know, 'Yeah, I rap too. Listen to my rap, plus I produce.' And that's a good thing too. I love Ski for that. A lot of people now are starting to know Ski as a rapper as opposed to when they didn't know about Ski at all."

Can't live without my radio

The impressive sales of Who R You even without distribution were stimulated in part by the strong support for the Ski-and-CMT-produced single, "What Is It," from the once local-leery Clear Channel station KMEL. KMEL, of course, was the second front of Ski's campaign. While he has generally maintained a radio presence as a producer, and even as an act in his own right, the level of rap superstardom Ski envisioned called for more than his own individual success. It required the support of a vibrant, hit-making scene in which Bay Area artists appeared on the radio, in the mix with nationally known acts from New York, the South, and LA. So he took the direct approach: He went to KMEL, willing to negotiate.

"If a veteran comes in with a résumé and gives you a hot record, and you don't take a chance on the record, you're basically saying that you don't want to try to make our area hot," he says. "That's all I ever said. If I give you a record that can compete with anything that's going on across the country, will you play it? They said yes. It was pretty much that simple.

"[KMEL managing director] Big Von told me clearly, 'You have to make records with a certain tempo. You have to tone down the profanity and subject matter.' I said, 'OK.' If you're trying to reach the commercial audience that radio reaches, you have to change your way of thinking, and I understood that."

Such deliberate catering to corporate dictates may have a Faustian ring to some ears, but Ski plainly feels this perspective is foolish. "Everything has a format," he points out, and getting KMEL to articulate one allowed Ski the opportunity to fulfill the format. The relative lack of stricture the station's ultimately vague requirements have placed on his creativity may be gauged by the Frontline's new single, "Bang It," from Rykodisc's recent revamped reissue of Who R You, retitled Now U Know. Compared to the hyper-boogie of "What Is It," "Bang It" is positively stately in its pace. What both songs share are the burbling techno noises, '80s synth sounds, and general club orientation found in much recent Bay Area hip-hop (see "Say 'Bay'"). Sounds that would have raised eyebrows in the mob-music milieu are becoming central to the Bay's digitally expanded tone palette.

Release the pressure

While Ski by no means deserves all the credit, his personal role in making the Bay Area hot again can't be denied. Yet even with all eyes on the Bay, and IMG's distribution deal already in hand, don't expect Ski to rush Apply Pressure out before he thinks it's ready.

"If you're gonna go out and make an album, you gotta stand firm behind it," he says. "And until I'm firm, my album will be out when it be out." The release is tentatively set for fall 2005.

With their own studio at their disposal, Ski and CMT have been able to update Apply Pressure at their leisure, replacing tracks that have become dated with ever more advanced material. Before I leave, they play me a few cuts, and I have to admit, I'm totally convinced. A spacious, aired-out reinvention of G-Funk, complete with radio-friendly singles, Apply Pressure is as far advanced as the duo claim. "This is some 2007 shit," Ski says proudly – though hopefully not literally. The Bay could use it right about now.

No comments:

Post a Comment