The post-2Pac pack

Did the death of Tupac Shakur throw Bay Area hip-hop into a tailspin? And is there really a "New Bay" rising?

By Garrett Caples

San Francisco Bay Guardian March 16, 2005

You can pick me up; I'll be posted on 10th Street

'Cause you know that's where I'll be

Stuck like a telephone pole.

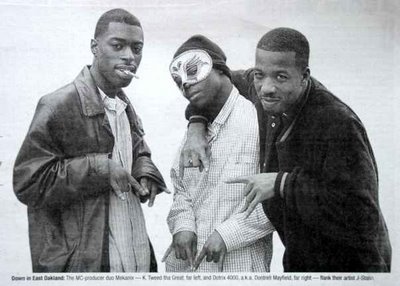

SO SINGS YOUNG rapper J-Stalin – a DJ Darryl discovery and former Richie Rich protégé – on a hook from his recent first mix tape, R-N-B. And it's true. As I roll up 10th Street in West Oakland's Oak Center, I see the short, wiry MC in the distance, standing in the middle of the street, talking on his cell. On the other end of the line, next to me in the car, is Dotrix 4000, a.k.a. Dontrell Mayfield, a former Digital Underground DJ turned MC-producer as half of the Mekanix. We've just driven from his house in East Oakland to pick up Stalin and bring him back to the Mekanix's studio, where they're finishing Stalin's debut, On Behalf of the Streets, for the duo's new label, Zoo Entertainment.

I live downtown, in a neighborhood no one calls Lakeside, about 20 blocks from where Stalin's "posted." In effect, I've spent my day doing a citywide doughnut. But Stalin's hood is worth it. A post-WWII black community inhabiting the structures of a middle-class Victorian past, Oak Center is funky as hell, beautiful blocks of houses in all shades and states of repair, dotted with buildings of a more recent vintage.

According to the fall 2003 Oakland Heritage Alliance News, the entire neighborhood was slated for demolition by the Department of Housing and Urban Development in the early '60s to make way for vast, anonymous housing projects. Only stubborn local resistance thwarted the plan.

'New Bay' vibed

Like Oak Center, Bay Area hip-hop is characterized by stubborn resistance, epitomized by 2Pac and still evident in Stalin's provocative choice of namesake. And that same spirit animates the community's reception of the catchphrase "New Bay."  Coined by Oakland MC Balance but popularized by Richmond duo the Frontline, the term "New Bay" has led to press in national publications like Vibe and XXL. The latter forecast a "resurrection" of Bay Area hip-hop based on Virgin's 2004 success with the Federation (from Fairfield) and Ryko's signing of the Frontline on the strength of their EA-SKI-produced hit "What Is It." Since the single broke into the rotation of the notoriously local-leery KMEL, 106 FM, the radio exposure has helped the group move 10,000 copies of Who R You (IMG), their 2004 independent debut, which will be updated and rereleased by Ryko as Now U Know.

Coined by Oakland MC Balance but popularized by Richmond duo the Frontline, the term "New Bay" has led to press in national publications like Vibe and XXL. The latter forecast a "resurrection" of Bay Area hip-hop based on Virgin's 2004 success with the Federation (from Fairfield) and Ryko's signing of the Frontline on the strength of their EA-SKI-produced hit "What Is It." Since the single broke into the rotation of the notoriously local-leery KMEL, 106 FM, the radio exposure has helped the group move 10,000 copies of Who R You (IMG), their 2004 independent debut, which will be updated and rereleased by Ryko as Now U Know.

Yet the phrase has also sparked a firestorm of controversy in the Bay Area hip-hop scene.

"I guess people are like, we done worked too hard to let people come in and say, 'We're the New Bay – fuck all the old shit,' " Dotrix 4000 says. "Those cats screaming, 'New Bay' – they ain't connected. But the underground is all connected. We've been connected."

As if cued, G-Stack of Oakland's Delinquents calls Dotrix 4000's cell. "I think it's bullshit," he says of the New Bay concept. At the same time, he lets it be known his gripe isn't personal. "I think the Frontline does have talent, and I wish them well. But it's about public perception. 'New' comes right after 'old.' "

Therein lies the problem. Like most forms of popular entertainment, hip-hop is extremely susceptible to the cult of the new. Careers start young and end early, unless you can adapt to rap's ever-changing circumstances. It requires indefatigable effort to stay on top of the game, the type of effort that's driven the Delinquents to record not one but two mix CDs – Have Money Have Heart volumes 1 and 2 (Dank or Die Records) – addressing the New Bay controversy. In a gesture of defiance, G-Stack and fellow Delinquent V. White enlisted the aid of Too $hort, Oakland's ultimate OG, for "Say Bitch," the lead single, which disses the New Bay in no uncertain terms.

Therein lies the problem. Like most forms of popular entertainment, hip-hop is extremely susceptible to the cult of the new. Careers start young and end early, unless you can adapt to rap's ever-changing circumstances. It requires indefatigable effort to stay on top of the game, the type of effort that's driven the Delinquents to record not one but two mix CDs – Have Money Have Heart volumes 1 and 2 (Dank or Die Records) – addressing the New Bay controversy. In a gesture of defiance, G-Stack and fellow Delinquent V. White enlisted the aid of Too $hort, Oakland's ultimate OG, for "Say Bitch," the lead single, which disses the New Bay in no uncertain terms.

The "2Pacalypse" Theory

To fully understand why a phrase so small could generate a reaction so extreme from a vet like G-Stack, we must invoke the "2Pacalypse" theory. Believers argue that Pac's death in '96 triggered an artistic decline that left Bay Area hip-hop incapable of attracting a national audience or major-label interest. Thus, the Frontline's bio on www.thefrontlineonline.com offers, "In the past six years, the Bay Area hip-hop scene has become stagnant, passing off replicas of established artists as new talent." Add a couple of years to account for the age of this blurb and we're back at 1997, without even mentioning Makaveli directly. The New Bay clearly presupposes the 2Pacalypse, insofar as there must be a grave from which to resurrect Bay Area hip-hop.

But the 2Pacalypse theory has at least two major holes that make it an unsuitable foundation on which to build an understanding of local hip-hop. For starters, it holds the artists responsible for the behavior of major labels. Yet even before 2Pac's death, major labels were getting cold feet in the Bay. On his Web site, www.guerillafunk.com, for example, Paris is vocal about his problems with Tommy Boy and then Priority regarding the political content of his work, which effectively stalled his career in the mid-'90s.

Or take the case of Ray Luv, 2Pac's partner in the Marin City group Strictly D.O.P.E. In 1993, Ray scored an independent radio hit with "Get Your Money On," on Mac Dre's Strictly Business Records. In 1995, with Dre in prison, Ray signed with Atlantic (once part of Time Warner and now with Warner Music Group), through Khayree's label, Young Black Brotha. Atlantic, he tells me, "put out my album about six weeks before Time Warner was about to fire Interscope over Death Row and 2Pac. So every record like Pac's basically got shelved because they didn't want you to blow up."

"I'd be in L.A. – I'm getting walk-ons on the biggest shows," he says. "Shows they couldn't get me, I'm getting. Atlantic moved me from there and sent me to Kansas City for five days. And I'm like, what just happened? Once we pissed each other off, they were sending me to hotels where my window faced a brick wall. It got weird, so I quit. I took from '96 to '99 off."

If this sounds like the paranoia of a could've-been contender, consider the source. Handsome and charismatic, Ray was already a proven hit-maker, as was Khayree. The label exec who couldn't exploit so close a connection to Pac for at least gold in 1995, when he was already the biggest-selling rapper ever, strikes me as an underachiever at best.

The second hole in the 2Pacalypse theory is the fact that the creative decline of Bay Area hip-hop never really occurred. With the major labels increasingly reluctant to sign acts, much of the scene went underground.  If you generated huge numbers, like E-40, whose 1993 EP, The Mail Man, debuted in the Billboard Top 20 with no distribution deal, you could force the majors to deal with you. (E-40 was quickly signed by Jive.)

If you generated huge numbers, like E-40, whose 1993 EP, The Mail Man, debuted in the Billboard Top 20 with no distribution deal, you could force the majors to deal with you. (E-40 was quickly signed by Jive.)

But it grew increasingly apparent that you could do without them. Indie scenes sprang up around artists like Blackalicious and the Soulsides/Quannum collective. In Oakland, Pam the Funkstress and Boots reinvigorated political rap on a national level as the Coup. Artists like Del tha Funky Homosapien left labels like Elektra to establish their own companies, while others, like the Delinquents, built huge followings from the ground up.

New bosses

By 1999, the revolution was in full swing, as independent tunes began to infiltrate the airwaves.  Among the local hits on KMEL that year was "That Man!," by the Delinquents, who went on to move 50,000 copies of 1999's Bosses Will Be Bosses (Dank or Die). By the end of the year, however, Clear Channel had bought KMEL, and G-Stack says he's been unable to get airplay since. (As of press time, KMEL musical director "Big Von" Johnson was unavailable for comment.)

Among the local hits on KMEL that year was "That Man!," by the Delinquents, who went on to move 50,000 copies of 1999's Bosses Will Be Bosses (Dank or Die). By the end of the year, however, Clear Channel had bought KMEL, and G-Stack says he's been unable to get airplay since. (As of press time, KMEL musical director "Big Von" Johnson was unavailable for comment.)

The Delinquents maintain a sizable fan base. "They are Oakland," Dotrix 4000 says, "in terms of selling records and reppin' our city. They can't throw a party and it's not sold out." But while successful acts like the Delinquents have countered the lack of radio exposure and label support through relentless hustle, it's unclear whether hustle alone can withstand the effect of the media actively promoting other artists as New Bay hip-hop.

On the phone, the Frontline are more conciliatory than they come off online. They seem genuinely nonplused by the furor the New Bay catchphrase has provoked. "Without the veterans," MC Locksmith of the Frontline says, "you have no Frontline, without the Too $horts, the E-40s, the Delinquents, the Luniz, without any of these cats." His partner, Left, concurs: New Bay was meant to be "a fresh way of looking at Bay music" rather than an attack. "Let everybody come up. Let's all make good music and all come up together."

I brought this statement to a number of rappers, and responses ranged from "They should've said that first" to "SKI should've known better" to "Fuck them niggas" – disappointing, but you can see their point. We're talking about a scene that still produces entire albums dedicated to Rappin' Ron of Bad Influenz, who died in a car crash in 1997. Most Bay Area rappers I've spoken to have real reverence for the tradition on which they build, and the New Bay concept offends their sensibilities.

Like the residents of Oak Center, they're proud of their community and don't want it wrecked by decisions made outside. In that light, the resentment provoked by the New Bay concept and the flurry of accompanying diss records shouldn't be ascribed to envy. They signify, instead, the stubborn resistance of a community that has survived without assistance and that refuses to cooperate, or be co-opted, except on its own terms.

No comments:

Post a Comment