By Garrett Caples

Mac Dre painting by Eustinove P. Smith

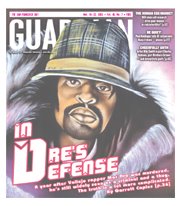

San Francisco Bay Guardian November 16, 2005

VALLEJO'S CRESTSIDE NEIGHBORHOOD occupies a tear-shaped square mile on the northeastern edge of town, wedged between a major thoroughfare and the freeways shuttling tourists to nearby Marine World. Centered on Crest Ranch Park, with bucolic street names like Miravista and Haviture Way, it was clearly designed as suburban space – modest homes with tidy lawns are laid out in traffic-impeding loops and dead ends, at once labyrinthine and insular. But far from being a commuter haven, Crestside is the toughest hood in Vallejo, home to a small, proud, extremely close-knit African American community that contributes a disproportionately large share of talent to Bay Area hip-hop.

The Mac may have been first, and Mac Mall may have been more famous due to his mid-'90s stint on Sony/Relativity, but the undisputed king of the Crest for more than a decade was Andre Hicks, better known as Mac Dre, a pioneer of Bay Area independent rap who scored his first underground hit in 1989 with "2 Hard 4 the Fuckin' Radio." A prolific artist with more than 20 releases – the vast majority released after 1996 on his own Thizz Entertainment/Romp Records label – the 34-year-old Mac Dre had already dropped three solo albums in 2004 and was more popular than ever when he was murdered on Nov. 1 that year, in a Kansas City highway shooting.

A year later, I'm in the Crest for a block party marking the anniversary of Dre's death. The Associated Press's subsequent characterization of the event as a "memorial service" attended by "150 people" fails to do it justice; there had to be a few hundred people in the street, mostly Crest residents of all ages who came together by word of mouth, without a permit, to celebrate Mac Dre in the most spontaneous manner possible.

"Dre loved his neighborhood," his friend and fellow Crestsider PSD told me earlier. "He loved people. As a result, people loved him."

The feeling is palpable in the Crest. I'm riding with another of Dre's friends, J-Diggs, in a van wrapped in an ad for his CD California Livin', Part Two, one of six new albums released that day on Thizz (see "Nation of Thizzlam," page 38). As we approach the block party, Diggs cranks Dre's "Boss Tycoon" and literally dances the van through the crowd, assisted by a half dozen dudes who jump on the running boards to rock us in time to the beat ("Dipped in sauce"–step–"I floss"–step–"I'm a boss"–step-step). People dance, or rather, parade, in front of the van as it struts around the block, and for a few moments I'm in the center of a communal outpouring of love, the kind usually reserved for folk heroes and saints. Dre's charisma had that effect on people, even his closest associates.

"He was the word of the Crest," affirms Dubee, a.k.a. Sugawolf, who started a neighborhood supergroup, the Cutthroat Committee, with Dre and PSD in the late '90s. "Just to get a response back from him was to know your existence in this turf shit was acknowledged."

The party rages on, rowdy but cordial, for a couple of hours: People drink, smoke, dance, and generally testify about Dre. At length, I return to the van, drunkenly devouring barbecue, when I hear two shots pop off. I quickly get acquainted with the floorboard.

Another volley – I count five shots – screams, and then another burst of gunfire. People are fleeing in all directions, by car and on foot.

Diggs packs his entourage into the van and sends us around the corner while he investigates. He immediately returns and pilots us out of Crestside's intricate maze. A 20-year-old Crest resident, Michael Clinton Banks, is dead of a gunshot wound. No one's sure who shot him or why – or even if it was intentional.

"I apologize for all the gunshots around your head today," Diggs later says. "But that's the neighborhood. That's what Dre rapped about. Some people who came to the Crest today was tourists, but tonight was living proof it's not a tourist attraction. To us in the neighborhood, that's routine."

Before the night is over, two other men – including Baygeen of the Crest Creepaz, whose CD The Thizzics Room also dropped that day – are shot near the crime scene. It's a bit much, even for Diggs: "Imagine getting shot the same day your album comes out!"

In the age of 50 Cent, in which being shot is fetishized as evidence of a rapper's street authenticity, being shot might help your career. But Diggs – who carries a bullet in his arm and one in his back, an inch away from his spine – knows it isn't a joke. It might kill you.

'They knew who they were after'

From the world-famous Tupac Shakur to local legends like Plan Bee of Hobo Junction, Rappin' Ron of Bad Influenz, and Eclipse of Cydal, the list of Bay Area rappers to die from gunshot wounds is as distinguished as it is long. The Crest itself had already suffered losses. The first rapper in Crestside, if not all Vallejo, Michael "the Mac" Robinson was fatally shot in 1991. Cecil "DJ Cee" Allison – a local mainstay who worked with both Macs – was killed in a drive-by shooting in 1995. Both incidents occurred in Vallejo, and both were reportedly cases of mistaken identity. In fact, with the exception of Shakur, none of the rappers mentioned above was an actual target – they were instead victims of proximity or misidentification, and the availability of firearms.

Dre's murder is different, however, as he was definitely the intended target of a hit, according to Kansas City police detective Everett Babcock, lead investigator in the case. "They knew who they were after," he says in a phone interview from Kansas City. Over the past year, Babcock has been piecing together a picture of the crime in terms of suspects and motives, though he cautioned it could take years before conclusive evidence comes to light. While he couldn't divulge details due to the ongoing nature of the case, he would confirm that his investigation turned up no evidence of any criminal activity on Mac Dre's part.

This is a detail worthy of emphasis, for the overwhelming impression left by media coverage of Dre's death was that he was a gangster whose criminal past had finally caught up with him. Most reports were based on a single Nov. 1, 2004, AP story, "Underground Rapper from Bay Area Killed in Shooting in Kansas City," which introduces Dre as a "rap star, who police say was also a member of a gang of robbers," before even printing his name. Only eight paragraphs later do we learn that this alleged gang membership was in "the early 1990s," and the story imperfectly distinguishes Kansas City from Vallejo police throughout, making his death seem connected to 15-years-old events.

Granted it'd be unrealistic to expect nuanced coverage of Dre's death on what happened to be the day before the most contentious presidential election in US history. But the way his death was reported not only denigrates Dre's artistic achievements, but also relies on the crudest of stereotypes (black male = rapper = criminal).

Rapper gone bad?

This is not to deny Dre's criminal record. Like many aspiring MCs, Dre began writing raps to stave off boredom in juvenile hall. After his release in 1988, he hooked up with the Mac and producer Khayree, who'd already put out the Mac's The Game Is Thick. (The last album Dre released, 2004's The Game Is Thick, Part 2, on Sumo, is a sequel/homage to his friend and mentor's underground classic.) Building a buzz with songs like "2 Hard for the Fuckin' Radio" and "California Livin' " (1991), Dre was clearly on his way to the majors when his career was derailed by an arrest for "conspiracy to commit bank robbery." Accused of being a member of the Romper Room Gang, responsible for a string of old-fashioned bank holdups in the Vallejo area in the early '90s, Dre wound up doing four years and four months in federal prison. But he maintained he was framed by Vallejo police, whose inability to catch the robbers he had mocked in the 1992 song "Punk Police."

According to J-Diggs, Dre's codefendant, who served eight years on the weightier charge of conspiracy to commit armed bank robbery, "the Romper Room crew was a group of youngsters growing up together – the name 'gang' was attached to us by the media. Our crew was only 11 deep and 9 of us went to the feds."

"I was into the bank robbery game," J-Diggs freely admits. "But not Dre. We was going to Fresno to rob a bank – me, my cousin, and another guy who was an informant wearing a wire. Dre ended up coming down there with us, to go mess with some girls. We had 32 FBI agents following us around for a couple of days.

"All they wanted out of Dre was to say, 'Yeah, I knew they was going to rob a bank. I didn't have nothing to do with it.' He could've went home, but he kept his mouth shut. Out of the crew, Dre is the only person I can say went to prison for nothing, for basically not telling on nobody."

What's really going on

Regardless of how you weigh such testimony – and Lt. Rick Nichelman, the Vallejo Police Department officer named by Dre on his recorded-over-the-phone-from-jail album, Back N Da Hood (Young Black Brotha 1993), maintains Dre was guilty as charged – one thing is certain: If Dre committed a crime, he'd done his time. Friends and collaborators describe the postprison Dre as completely focused on music, to the exclusion of extracurricular income.

"Dre wasn't a criminal," PSD insists. "He wouldn't know how to steal. I heard him denounce pimping, the whole getting supported from a female, three or four Gs every night. He said, 'Man, I just want to rap.' He was dedicated."

Dubee similarly recalls Dre's encouragement to concentrate strictly on music: "I'm a street rapper. He used to get mad at me because I'm so street. 'Dubee, you got to leave this street shit alone sometimes.' We didn't know it, but Dre had stopped looking at us as 'the little cuddies.' He was like, 'Y'all with me now.' "

"He gave a lot of people the opportunity to do music," says North Oakland rapper Mistah F.A.B., who became tight with Dre in the last year and a half of his life. "He was a good dude, a philanthropist. He didn't base a lot of things on the materialist ideology a lot of rappers have. I've never heard anyone say anything bad about Dre."

Such universal goodwill in the notoriously factional world of Bay Area hip-hop is rare, but stories of Dre's own generosity to his fellow artists are legion. Perhaps the most illustrative comes from producer One Drop Scott, who himself was brutally beaten and left for dead in an incident at the Berkeley Marina a couple of years ago.

"When I got out the hospital, I was at Harm's studio at the Soundwave. I ran into Mac Dre. He listened to what I'd been doing since I got back. He was loving that I was still doing my thing. He came back the next day, handed me a fat-ass check. 'Drop, I need you, bro.' He was the first to chisel me off and make sure that I was cool."

Clearly Dre appreciated defiance in the face of overwhelming odds and appalling setbacks. When he was about to blow up, he was sent to prison for what would be considered his prime in an age-conscious industry like hip-hop. When he got out, he had to start over at a time when the Bay was ice cold; even then, he consistently moved around 30,000 units, with the occasional disc selling more than 60,000 copies, according to SoundScan reports. When he started getting hot again after the Treal T.V. (2003) DVD, he warmed up the Bay with him. When he was about to blow up again, he was murdered.

When all is said and done, Dre was the one who was robbed.

No comments:

Post a Comment